The UK government is commited to tackling these skill imbalances as reflected in a number of recent initiatives

The UK government is commited to tackling these skill imbalances as reflected in a number of recent initiativesThe United Kingdom has enjoyed record-high employment levels in recent years and one of the lowest unemployment rates among OECD countries.

However, labour productivity growth, which is closely linked to the use of skills, remains weak. This has been translated into weak growth in wages. Job prospects of many adults are also hurt by their poor literacy and numeracy skills.

Improving the alignment of skills supply and skills demand could help to boost growth, productivity and earnings in the UK.

To assist UK policymakers in meeting this challenge, the OECD will release its Getting Skills Right: United Kingdom report during a launch event held in London and in partnership with JPMorgan Chase Foundation and IPPR.

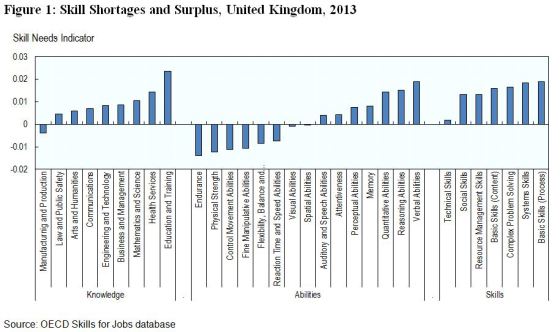

The UK report is one of a series of country studies that look at the issue of skill imbalances, building on evidence from the OECD’s Skills for Jobs database. The launch event also represents the culmination of the IPPR’s three-year project on New Skills at Work.

Skill imbalances are high in the UK: 40% of workers are either over-qualified or under-qualified for their job, and a similar number are working in a field unrelated to the one in which they studied.

For instance, more than half of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) graduates in the UK end up in non-science-related occupations, such as finance or the public sector.

Many STEM graduates are tempted to enter non-STEM occupations due to lucrative financial incentives despite shortages in mathematics and sciences.

In other cases, field-of-study mismatch arises due to low demand for a given field-of-study. When workers must accept jobs for which they are over-qualified because they cannot find a job in their field-of-study, then they suffer wage penalties and lower job satisfaction. About a third of workers who are mismatched by field-of-study in the UK fall into this group.

Educational attainment has been rising in the UK, with 42% of adults having a tertiary degree, compared with 34% across the OECD. However, demand for tertiary-level qualifications is low relative to the supply of tertiary-qualified workers.

Furthermore, many young adults—including university graduates—have low literacy and numeracy. Poor literacy and numeracy leave young adults ill-equipped for the demands of today’s labour market, in which cognitive skills are in shortage while manual and physical skills are in surplus

The UK government is commited to tackling these skill imbalances as reflected in a number of recent initiatives.

Recent reforms to the regulation of apprenticeships aim to bring training content more in line with employers’ needs, and the new apprenticeship levy should encourage employers to take more responsibility for training.

A recent UK green paper also sets out an industrial strategy that has a strong skills focus, and proposes investing more in science, research and innovation which could promote stronger demand for higher-level qualifications, the supply of which currently exceeds demand.

Other efforts include: the Union Learning Fund which promotes learning in the work-place with a focus on older and low-skilled workers; the Sector-Based Work Academy program which has proven successful in activating and reskilling the unemployed, the requirement that 16-18 year olds as well as the introduction of income-contingent loans for further education which facilitate access to adult training.

Nevertheless, the OECD’s Getting Skills Right: United Kingdom suggests that additional actions should be taken to bring skill supply more in line with skill demand:

- Strengthen career guidance services

There should be more interactions between employers and secondary schools in the delivery of career guidance for students. Expand access to career guidance services for all employed workers, in order to facilitate transitions in the face of evolving skill demand.

- Encourage lifelong learning

Advanced Learner Loans for further education could be made more attractive to workers, e.g. by tying waivers of repayment to employment in certain shortage occupations. Allowing the loans to be applied to modules, rather than only to full qualifications, would also increase flexibility (as suggested in the recent Taylor review).

- Raise awareness about the value of training

More efforts need to be made to convince employers of the business case for training; otherwise the new apprenticeship levy is unlikely to be successful in inciting new and high-quality training.

- Develop a skills utilisation policy

Develop a skills utilisation policy by funding a set of pilot initiatives to test “what works” in terms of adapting work organisation and management practices to make better use of employees’ skills, drawing on good practice examples from countries like Finland. Stimulate demand for higher-level qualifications by investing in R&D in order to harness productivity benefits of the digital revolution and reduce over-qualification.

The full set of policy recommendations and good practice examples from other countries can be found in the full report. More detailed findings from the Skills for Jobs database are summarised for the UK in the accompanying country profile.

Recruiters love this COMPLETE set of Accredited Recruitment & HR Training – View Training Brochure